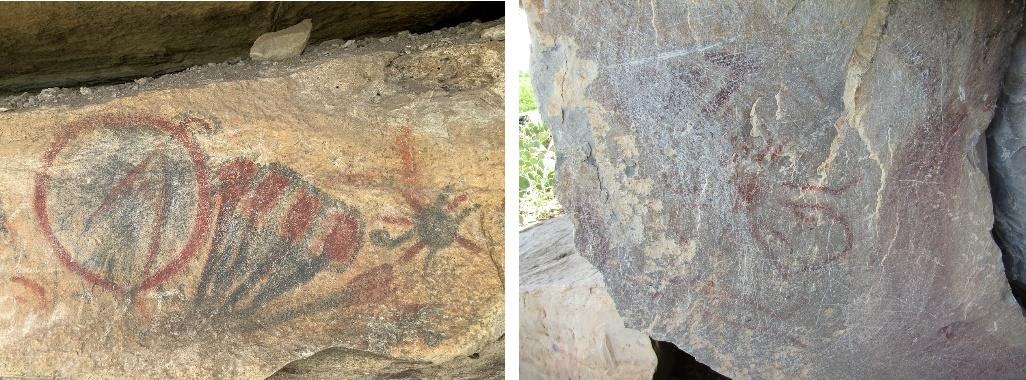

There are three general phases of rock art at Paint Rock. The oldest is Pecos River Style, which theoretically spans an unlikely 5,000 years. Modern rock art scholars are presently attempting to further refine the phases of Pecos River Style based on significant variations within the “style.” At Paint Rock, we have identified at least two, and maybe three, different phases of Pecos River Style. The oldest appears to match closely with rock art from the Lower Pecos that has been conclusively dated to more than 3,000 years old. Once we are able to run radiocarbon dates on the rock art from Paint Rock, we will have a better understanding of the antiquity of this art. There is only one definite solar interaction (the Flower Panel) that we ascribe to this time period, although there are other possibilities based on the age of the rock art involved.

The second phase of rock art at Paint Rock is the Jumano phase. We don’t have a very good understanding of when this phase began, but it lasted up until the late 1700s. Most of the major solar interaction panels at Paint Rock fall into the latter Jumano phase and, at their earliest, seem to date from the 1600’s. Almost all of the over 50 solar interactions with the rock art occur with rock art produced during this time period.

The third phase of rock art begins well into the historic period. The Apache were here beginning around 1700 and the Comanche began showing up on the scene by 1750. There is no rock art that we can definitively assign to the Apache, but there are several that appear to have been created by the Comanches. If the Comanches were the ones who painted the Mission San Sabá panel, then they were painting here by at least 1758. The two paintings that are identifiable as the signatures of Comanche chiefs, the Asa Habbe Stars and the drawing of Buffalo Hump, would be from the mid-1850s and would be the Comanche counterpart to the Anglo graffiti. There are no definite solar interactions from this time period, and only a couple of problematic ones.

What sets Paint Rock apart from almost every other rock art site in North America in not only the number of its solar interactions, but also their sophistication. The solar interactions with the rock art at Paint Rock are not like anything else ever recognized -- anywhere. The entire site is not only organized as an almanac, but manifests a very basic structural philosophy of the rock art that is consistently borne out with each new discovery.

The entire bluff of which the Paint Rock archaeological site is a part is around 1500 m. in length, but the site itself is restricted to 300 m. in the central part. It is bookended by the Changing Woman Birth Panel on the east end and the Decapitation (Death) Panel on the west end. There is nothing to the east of the Birth Panel and nothing to the west of the Death Panel (which, significantly, ends at a natural spring). Both of these panels interact with the sun on the winter solstice, with the beginning of the site and ending of the site emphasizing the same day and encapsulating an annual cycle (from winter solstice to winter solstice).

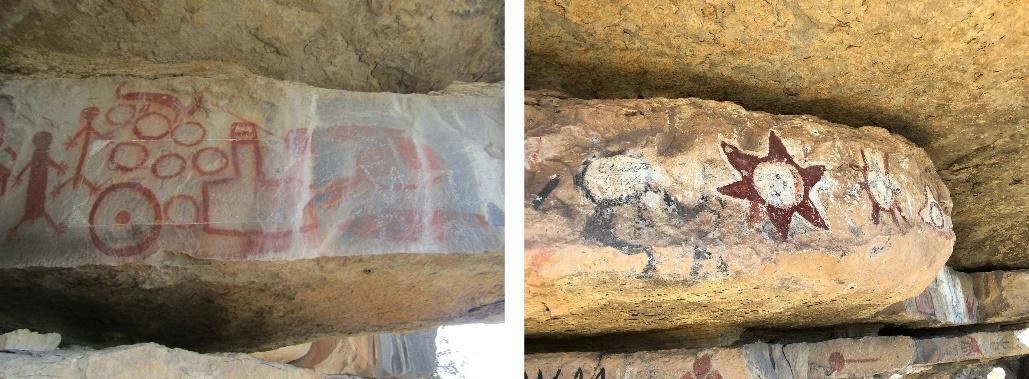

For 300 m. in between those two panels is found a dense collection of rock art, mostly pictographs but with the occasional etched petroglyph (including the beautifully executed Water Bearer). We have recorded well over 50 (and constantly growing) solar interactions with the rock art that take place throughout the year, mostly on the equinoxes and solstices, but several on the cross-quarter days. Some of these solar interactions are spectacular.

While the pre-Columbian peoples and cultures that inhabited Texas, the American Southwest, and parts of Mesoamerica were hardly homogenous, elements of shared cosmology and understandings of the world appear throughout the region. In particular, the concepts of time and movement underlie the core of their understanding of existence. In fact, the ancient Mesoamerican concept of the divine cannot be understood unless it is understood as a split personality that was constantly changing. Practices that we would categorize as “religious” today were all time-based, dependent on both natural rhythms and numerical calculations. Correspondingly, anything that kept track of that time was just as sacred as the time it tracked.

In the divinatory almanac pages of the Mesoamerican codices, all time-keeping systems can relate to, and have their own influence on, a specific date in time (such as an eclipse or the birthdate of a king). These Mesoamerican systems include the 365-day calendar, the 260-day calendar, the 20-day “month,” the Venus cycle, the Nine Lords of the Night, and the lunar cycle – all of which carry their own system of influences. While Paint Rock does not incorporate the exact same systems, it probably did incorporate all time-measuring systems that were known to the people who painted the rock art. These included the 365-day calendar, the solar day calendar, and the sequencing of events on the annual and day calendars. Some of the solar interactions at Paint Rock also correlate with shadow lengths – 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8. (Lunar and Venus cycles were probably also in use because both lunar and Venus imagery appear in the rock art and are involved with solar interactions.)

The Mesoamerican codices count time by dots and glyphs. Paint Rock, because it is written on rocks and not on paper or parchment, can count actual time through its solar interactions, something the codices cannot do. Some of the more spectacular examples of this from Paint Rock are the Winter Solstice Marker, the Equinox Marker, and the Hummingbird Panel, all of which exhibit extraordinary solar interactions.

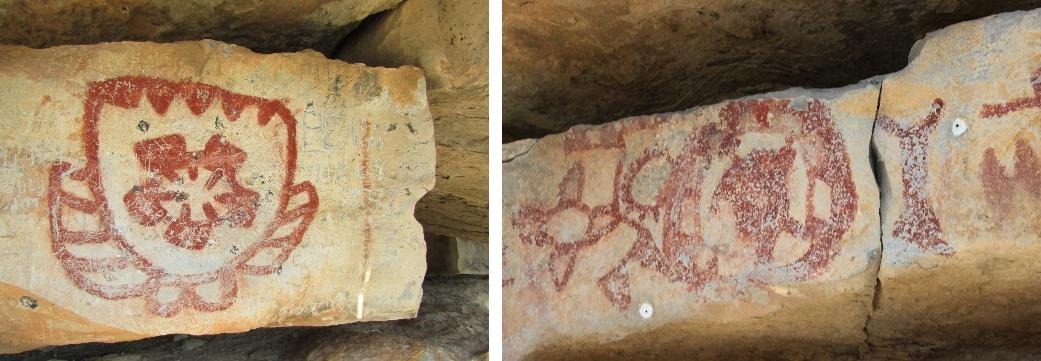

The Winter Solstice Marker is remarkable in two respects. The first is its numerology, which matches up closely with Uto-Aztecan speaking cultures. Five, for instance, is the number of completion. Nine represents the underworld. The seven cavities in the middle are reminiscent of Chicomoztoc, the seven caves of creation to the Aztecs.

The second important aspect of the Winter Solstice Marker is that it incorporates the idea of the New Fire Ceremony, practiced by most Mesoamerican and southwestern cultures on the winter solstice. At exactly solar noon on the winter solstice a point of light (representing a fire drill) penetrates the center of the seven cavities in the middle of the figure. Two minutes on either side, it doesn’t really work. The people who drew this figure calculated solar noon to the minute. That is impressive.

With the Equinox Marker, around 3:37 pm on the equinox this odd figure perfectly walks the line. This panel has a lot of eclipse imagery in it and may refer to a total solar eclipse that occurred on March 22, 1727 – one day after the equinox -- thereby explaining why it looks so much like an equinox panel. Its sequencing with other nearby rock art only reenforces this theory. If it is indeed an eclipse panel, it is the only one recognized in the rock art of North America.

And then there is the Hummingbird Panel, a fairly simple rock art panel whose cosmological sophistication is unmatched. This panel plays out over the winter solstice, the spring cross-quarter day, and the vernal equinox. It tells a story about the birth of the sun that is recounted in Sahagun’s Florentine Codex. Incredibly, the last thirty minutes before sunset on the vernal equinox go like this: a) at 7:11 pm the sun takes on the shape of a hummingbird with its beak touching the painted red hummingbird at its tailfeathers while at precisely the same moment the lower sun/shadow line cuts the ballplayer and the ball in half; (b) at 7:32 pm the solar hummingbird has moved up to decapitate the red hummingbird while the lower sun/shadow line decapitates the ballplayer; and c) the last light of the sun as it is setting at 7:38 pm barely touches the tailfeathers of the white hummingbird immediately before it fades out. Summer Seigler’s discussion of this panel has placed it as the most sophisticated solar interaction panel in North America.

All of these panels, and several more, are time-measuring devices similar to those contained in the divinatory almanac pages of the Mesoamerican codices. And like the codices, they presumably were tied into actual events that existed at a specific moment in time. We have our suspicions about several panels, but without a pre-Columbian narrator (as exists with the codices), we do not know what the events were. However, that changes after Spanish contact. The three panels and one date created after contact all represent specific moments in time.

The San Saba Panel represents events that happened on March 16, 1758. The Priest and Cross probably represent the moment of contact with either the Castillo and Martín 1650 or Mendoza 1684 Spanish expeditions (both of which had priests with them and probably came within eyesight of Paint Rock). The picture of the Mission San José in San Antonio represents the widely-practiced (at that time) Feast of St. Joseph that occurs every year on March 19 (the day before the vernal equinox). And then there is a date written in pen and ink that literally says “Juno neuevey ano 1598.” There is no graffiti around it – just the date. In the Julian Calendar, this was the day before the summer solstice.

Native Americans found the Spanish calendar system to be a sacred device in that it could predict how far away from a given date any other date was. Also, as a liturgical calendar, and similar to the indigenous calendar systems, specific days had their own special meanings and influences. By assimilating this date into their almanac system, they were able to incorporate the spiritual essence of the Spanish calendar system into theirs. (This 1598 date, by the way, is the oldest written date in the United States, predating the 1605 graffiti at El Morro by seven years.)

The rock art at Paint Rock is dense and localized, being bounded by the Birth Panel on the east and the Decapitation Panel on the west – beginning with the winter solstice and ending with the winter solstice. In between, several major panels either mark a specific date or tell a story relating to a specific date (or take place over several days). These dates all have their own essences and influences. The symbols and measurements of time in the rock art panels at Paint Rock, like the Mesoamerican calendar systems contained in the codices, are the manifestations of religious belief systems that placed time and the measurements of time at the forefront. Through the integration of the rock art with the cosmos, their creators could infuse them with the same sacred forces that powered creation, making them not just static representations of the divine, but active participants in its continual recreation of itself. That is the magic of Paint Rock.